What do psychologists study?

Psychology is usually defined as the study of mind, brain, and behavior or a combination of the three. But that definition by itself does little to distinguish psychology from biology, anthropology, or sociology. Many biologists, for example, are concerned with behavior and the brain, both human and otherwise. Sociologists and anthropologists are both interested in human behavior, often as it intersects with beliefs, attitudes, and other things going on inside people’s minds that we would generally think of as psychological.

What distinguishes psychology from related fields?

There are perhaps 3 ways to best distinguish psychology from these other fields.

1. Psychology focuses on “mind”

The first goes back to that definition itself. Although there have been brief intervals when psychology didn’t care much about mind (see behaviorism), these were fleeting periods. That is, while psychologists are often interested in behavior or in the physical structure of the brain, they are almost always also interested in how that structure or that behavior is connected to the mind: that is, to what people think or feel, whether at a conscious or unconscious level. Sometimes biologists, anthropologists, or sociologists are interested in mind too, but the more that becomes a central part of what they care about, the more interaction and overlap they have with psychologists.

2. Psychology has a distinct intellectual history

The second aspect of what distinguishes psychology from these other fields is more a matter of historical accident. Like other academic disciplines, biology, anthropology, sociology, and psychology each have distinct histories, traditions, and leading figures who helped make that history and tradition. As such, each discipline has tended to focus on particular methods and topics that help define the field. Sometimes there is a lot of overlap, sometimes there is less. You would need to study each field to get a good sense for how topics and methods differ, because it’s not well captured by the definition or by a brief mention of a few subjects.

3. Psychology uses specific practices and techniques

The third distinguishing feature concerns the practice of psychology; that is, what do psychologists tend to do as distinct from people in these other fields of study? This leads us to the second level of analysis: the two major types of psychology.

Popular online programs

www.degreechoices.com is an advertising-supported site. Featured or trusted partner programs and all school search, finder, or match results are for schools that compensate us. This compensation does not influence our school rankings, resource guides, or other editorially-independent information published on this site.

Scientific research psychology versus applied health psychology

The majority of professional psychologists work in the applied health professions. They work with people to help them gain insight into their own psychology, often because they are dealing with mental disorders. Biologists, anthropologists, and sociologists do not do this. One group of medical doctors do – psychiatrists.

Psychiatrists tend to use language and other behavioral interventions in much the same way as other medical doctors do: to help find out what is making their client sick so as to be able to prescribe the right kind of medical treatment, usually psychiatric drugs like SSRIs, anti-anxiety medication, or sleeping pills. Health psychologists, on the other hand, focus on behavioral rather than biomedical interventions. These interventions usually involve talk as the primary tool for treatment.

Of course, the distinction is not clear cut, and some psychologists may prescribe medicines and many psychiatrists will use psychotherapy as a tool. More often, the two types of practitioners work together, referring a client who they feel needs medical treatment or talk therapy, depending on their own qualifications and judgment.

Some psychologists prescribe medicines and many psychiatrists use psychotherapy as a tool. Often, the two work together.

This is what distinguishes health psychologists from all of the aforementioned scientific fields, since biologists, anthropologists, and sociologists do not work in the health professions. Yet, there is an entirely separate and large group of psychologists who do not work in the applied health professions and who are more difficult to distinguish from other social sciences: research psychologists. Other than the fact that both kinds of psychologists share the same name, studied in psychology departments, and had some of the same introductory-level undergraduate course requirements, this latter group of psychologists is probably more like sociologists, anthropologists, and biologists than applied health psychologists, because they identify as scientists, do research, and rely on scientific methods.

What do research psychologists do?

Research psychologists conduct controlled experiments, usually in labs or classrooms. They almost always start with a hypothesis they intend to test quantitatively rather than just questions. They are overwhelmingly concerned with species-wide generalizations rather than what makes different groups of people unique. Sociologists often start with hypotheses as well, but they are less inclined to be experimental. They give surveys with large samples and analyze the responses to test their hypotheses or to answer their questions.

The distinction between practical health psychologists and scientific research psychologists is so central to psychology that it would not be a large stretch to consider them 2 entirely separate fields of study.

The distinction between practical health psychologists and scientific research psychologists is so central to psychology that it would not be a large stretch to consider them 2 entirely separate fields of study. As mentioned already, research psychologists arguably share more common training and epistemological commitments with scientists from other fields of study than they do with health psychologists.

» Read: Studying psychology: 38 statistics to know

Psychologists use surveys, too, but usually with much smaller samples and with an experimental design built in. The survey will be given to people in two different experimental conditions, with responses meant to test some hypothesis about the difference between the 2 experimental groups. Biologists often use similar experimental designs to psychologists, but in order to explain biological systems rather than mental states, and so surveys and other verbal reports are far less common for biologists. Psychologists’ experiments almost always concern mental states: thoughts, beliefs, and feelings.

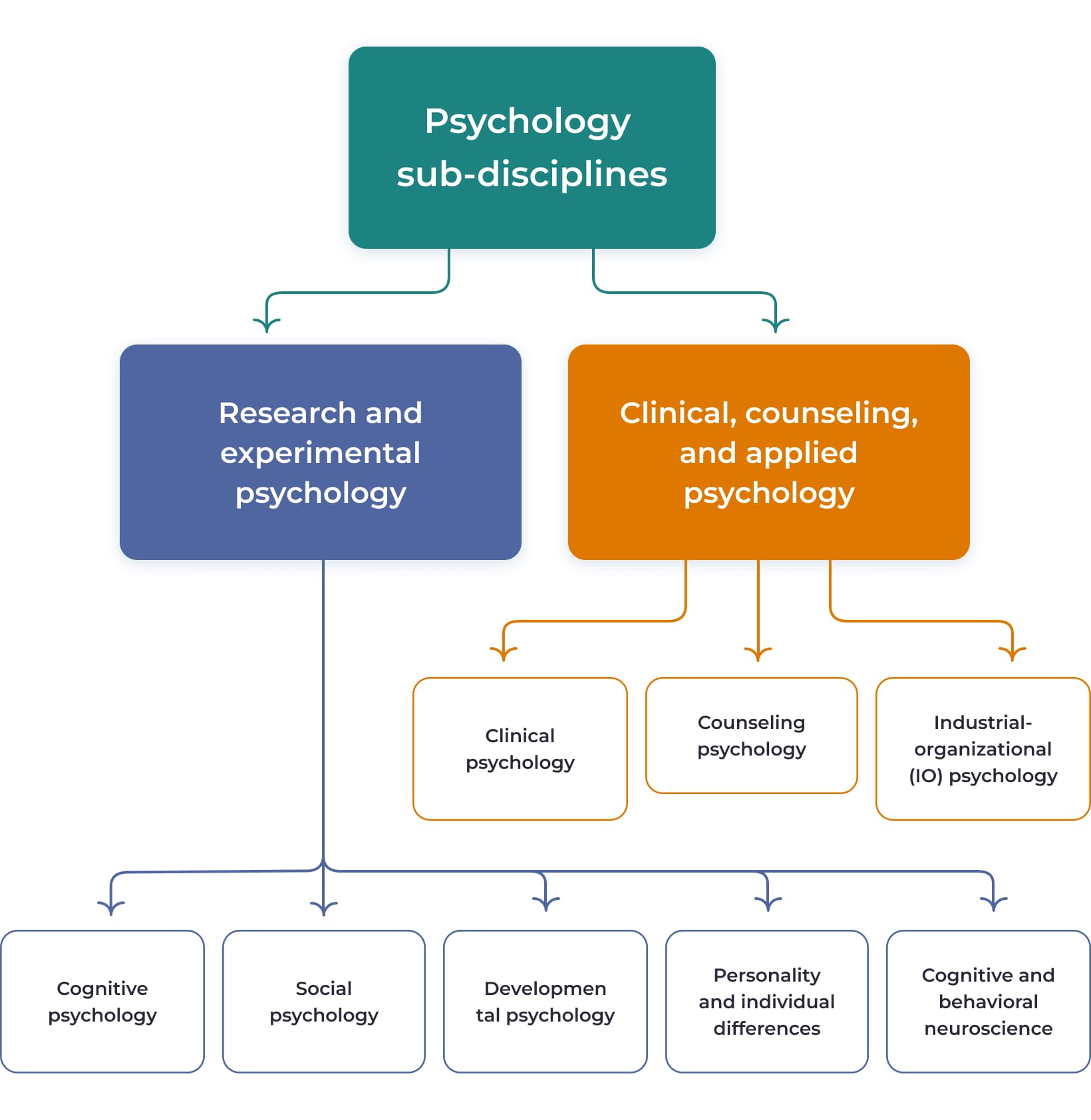

While this top-level distinction is important, the real meaning behind what and how psychologists study comes down to the sub-disciplines in each field.

Psychology sub-disciplines

As the sharp distinction between scientific research psychology and applied health psychology suggests, the sub-disciplines themselves are best understood as subsections of each of these 2 top-level categories. Perhaps the best source for identifying the major subdisciplines comes from the U.S. government’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), and the detailed list they developed to evaluate and quantify the field of psychology throughout the U.S. (by far the largest global market for both the health and research psychology domains).

» Read: The best grad programs in psychology

The NCES update their list based on how psychology departments themselves divide the field, and so by what psychology students are most likely to study. Their title for the health psychology category is, “Clinical, Counseling and Applied Psychology”, and their title for the research psychology category is “Research and Experimental Psychology”. We’ll use these inclusive names as the header for each top-level category. The subcategories here also closely map on to the NCES sub-categories, although we’ll pare their list down to the most relevant sub-fields.

Research and experimental psychology

The following are key sub-disciplines in research and experimental psychology. Research psychologists use controlled experimental design to test hypotheses about the intersection between mind, brain, and behavior.

1. Cognitive psychology

First in the NCES’s list are cognitive psychology and psycholinguistics. That is no accident, as it is almost fair to say today that all research psychology is now cognitive psychology. As the name implies, cognitive psychology is concerned with cognition, that is, the mind part of the “mind, brain, and behavior” triumvirate of psychology: how people think and feel.

Cognitive psychology itself was largely a response to an earlier dominant scientific perspective in psychology – behaviorism. Behaviorists were primarily concerned with how to make psychology more like the “hard” sciences, and their answer to that question was to limit the field of psychology to only what scientists could directly observe and measure.

As the name implies, cognitive psychology is concerned with cognition, that is, the mind part of the “mind, brain, and behavior” triumvirate of psychology.

Since what is going on inside the head is particularly hard to observe and measure – especially before the advent of new brain scanning technologies – behaviorists’ solution was to treat the mind (cognition) like a black box and avoid making conjectures about it. Instead, they dedicated themselves to studying external stimuli and behavioral responses to those stimuli. That commitment was sometimes brought to absurd extremes, with some behaviorists suggesting that cognition itself is not necessary to the link between stimuli and responses and others suggesting that because we cannot see or measure it, the most parsimonious explanation is that cognition does not exist at all.

Cognitive psychologists inspired in part by the computer revolution, pointed to the obvious absurdity of these extreme positions. Of course cognition matters: we might not be able to observe and measure it as effectively as stimuli and behavior, but we can all “see it” first hand from introspection. Perhaps more importantly, human behavioral responses vary widely to the same stimuli, making clear that while behaviorism might be a useful tool in the psychologists’ methodological inventory, it is not sufficient to understand psychology. Using the computer central processing unit as an analogy, cognitive psychologists try to model and understand how the mind processes information.

2. Social psychology

Social psychology may be the second-largest sub-discipline in research psychology. As suggested already, most social psychologists are in fact cognitive psychologists, but their particular focus is on cognition within a social context: how does the behavior of others, or the mere presence of others, influence how we think and feel?

Humans are social animals; our brains develop and are evolved for social contexts and social reasoning, and many would argue a central aspect driving human evolution is directly related to social intelligence. Social psychology has historically provided much of what makes it from research psychology into the public domain, as the social domain is arguably what makes psychology interesting to most people.

3. Developmental psychology

As the name implies, developmental psychology is concerned with human development across the lifespan. There is a strong bias in the field toward child development, perhaps as childhood is the period when the most extensive and noticeable change happens; perhaps because it is the period when the building blocks for the rest of development are formed; or ,perhaps as a historical accident with earlier – and continuing – commitments in the field of psychology that the most important psychological development occurs in childhood. That said, many developmental psychologists focus on adult development. As with cognitive and social psychology, developmental psychology is one of the major sub-disciplines.

4. Personality and individual differences

A fair distinction between research psychology and cultural anthropology is that while anthropologists are concerned with what makes people different from one another, psychologists are concerned with what makes us all the same. There’s one major exception to this generalization, however, and that is the psychology sub-discipline of personality and individual differences.

Unlike anthropologists, psychologists interested in individual differences are generally not interested in the role of culture, beliefs, or the physical environment in what makes people different, but – like other psychologists – are primarily concerned with how cognitive processes (mind) and brain might explain those differences.

Personality psychologists tend to focus on constructs they see as somewhat permanent characteristics that explain individual differences. Other psychologists in this domain focus on personality traits and many focus on more environmental and developmental influences on what makes people different from one another.

5. Cognitive and behavioral neuroscience

The last major sub-discipline in research psychology is also the newest of the bunch. Neuroscience is the (usually) interdisciplinary science of the nervous system: the interaction neurons (brain cells) have with the rest of our biology to impact how we think, feel, and behave. “Cognitive and behavioral” here makes it more psychological. Much of neuroscience is focused more on brain biology – the physics of the communication between neurons (brain cells), or on the philosophy of how one gets from brain (biology) to mind (cognition).

Cognitive & behavioral neuroscience, however, are concerned with the scientific study of how that biological brain material impacts how we think, feel, and behave. While people have been thinking about and studying these questions at least as far back as the ancient Greeks, several very recent technologies, most notably functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), have provided a largely non-invasive way to look at the brain in action.

To a large extent, this has allowed us to observe and measure the black box that some behaviorists were ready to discard from the field of psychology altogether just a half century ago. These new technologies have led to a meaningful coming together of brain biology and cognitive psychology, creating what is almost certainly the fastest-growing and best-funded area of research psychology.

Clinical, counseling, and applied psychology

The following are the major sub-disciplines within clinical, counseling, and applied psychology. These psychologists tend to focus on helping people with psychological challenges using behavioral interventions (usually talk therapy).

1. Clinical psychology

Clinical psychology represents what likely first comes to mind for most people when they conjure up the image of a psychologists. Freud or Jung, Tony Soprano’s therapist, the client lying on a couch or sitting in an armchair talking about their childhood or their fears. Clinical psychologists must go through extensive training and certification in order to practice their trade, and they get certified to work in a particular state, much like a doctor or lawyer.

As with doctors and lawyers, they usually focus on a particular school of psychology, so that they may become person-centered therapists, or cognitive-behavioral therapists, or psychoanalysts (the school founded by Freud). Most people licensed to conduct psychotherapy are clinical psychologists. It is a highly regulated field and universities that wish to train clinicians must be certified to do so.

» Read: What are the main differences between a counselor and therapist?

2. Counseling psychology

Counseling psychology is much like clinical psychology except that the requirements for certification and training are not as rigorous. Whereas clinical psychologists must do extensive training in how to diagnose and evaluate various psychological disorders, counseling psychologists are more focused on the helping aspect of psychology and are more likely to work in school or community settings.

» Read more: Types of counseling degrees

3. Industrial and organizational (I-O) psychology

I-O psychology takes insights from the field of health psychology and applies them to the business world (industries, organizations, etc.). I-O psychologists work inside companies to help create a healthy organizational culture and to look at how the company environment promotes or hinders healthy psychological functioning. For people interested in both business and psychology, this is perhaps the ideal domain.

There are many other sub-fields in clinical, counseling, and applied psychology, including sports psychology, forensic psychology, geropsychology (the psychology of old age), and family psychology, but the above cover some of the main subdisciplines.

Areas of specialization

There are literally thousands of areas of specialization that will have communities of other psychologists and non-psychologist specialists with conferences, specialized lexicons, favored research topics and methods, and often their own peer-reviewed journals. Sometimes these areas become large enough or their theoretical and methodological commitments are distinct enough that they form new sub-fields of psychology with their own departments.

For example, evolutionary psychology, political psychology, and cultural psychology are all domains that have grown enough in recent years to have dedicated departments. More often they remain “mere” shared topics of study within a particular sub-field. Therefore, rather than trying to cover the spectrum, this section will just give a couple of examples from my own background in psychology, since I know them best and they give a good sense of how diverse and specialized psychology has become.

My professional journey as a psychologist

I started my training in a cultural psychology program. Cultural psychologists are interested in how the practices, values, and beliefs that are widely shared and reinforced within a particular group (“culture”) influence basic psychological processes like emotions, categorization, or reasoning. They may also study how psychological processes influence the creation of culture. There are a handful of cultural psychology programs in North America that I was particularly drawn to because I wanted to study moral sensibilities and it was clear to me that culture played an important role.

I was particularly interested in how and why moral sensibilities exist in humans at all, and so along with applying to a couple of programs at the intersection between anthropology and psychology (as cultural psychology is), I also applied to programs in evolutionary psychology and comparative psychology.

Evolutionary psychology is primarily concerned with how biological evolution has shaped human psychology. Comparative psychology looks at the psychology of other animals as a way to gain insight into human psychology. Both fields have explored human morality in ways that resonated with me. So, right at the beginning, I was considering three distinct sub-disciplines in psychology that were too specialized to make the above list of sub-disciplines (cultural psychology, evolutionary psychology, and comparative psychology) and had a topical focus (morality) that each sub-field was exploring in a slightly different way.

Once I began my studies and had to make the practical decision of what my particular doctoral research would involve, the focus on morality switched to an interest in the distinction between rational and non-rational ways of knowing and deciding. My research moved into the field of judgment and decision making and rational choice theory, which also have dedicated departments largely responsible for the field of behavioral economics in the neighboring social science field of economics.

My way of studying moral sensibilities was to try to look at how non-rational processes are central to domains we think of as ideally rational. I decided to study the psychology of gambling, since gambling has been a central metaphor in rational choice theory and is a lot easier to evaluate from a mathematical, normative perspective, but which also clearly involves non-rational aspects.

Environmental psychologists focus on how the environment influences basic psychological processes, much as cultural psychologists look at how culture-specific beliefs and practices influence psychology.

I conducted my research in casinos. As a cultural psychologist, I was already particularly interested in gambling subcultures and in how casino environments contribute to gamblers’ strategies and beliefs. I quickly realized that the physical designed casino environment has a big impact on both, which moved me towards a new field of psychology, environmental psychology. Environmental psychologists focus on how the environment influences basic psychological processes, much as cultural psychologists look at how culture-specific beliefs and practices influence psychology.

To me, there is a natural affinity between the 2 fields, particularly when the environments themselves are products of human culture, as anyone who has spent a weekend in Las Vegas can tell you. (Although casinos are perhaps the lowest form of cultural artifact.)

Now, I could go on, as my research and experiences in environmental psychology have brought me to new areas of specialization, but the point would be missed. While I am certainly a bit of an outlier with respect to how many distinct psychology sub-disciplines I have crossed (evolutionary psychology, cultural psychology, environmental psychology, comparative psychology, judgement and decision making, moral psychology, the psychology of gambling, rational choice theory), the main point is that almost any topic you can imagine can be studied in psychology, often from various perspectives, even crossing between psychology and other fields of study.

Indeed, if you find a topic or approach that you are passionate about, you will probably be able to find a place that specializes in it. If that place doesn’t exist yet, there’s a good chance it will in the next decade or so, as the same socio-cultural factors that drove you to be interested in the topic are likely driving many other scholars as well. Psychology is a thriving and always diversifying and changing field. As long as you are interested in some aspect of the intersection between mind, brain, and behavior, you will most likely find people to work with.

About the author

About the author

Dr. Will Bennis, Ph.D., is a cultural and environmental psychologist focused on ways in which culture and built environments interact to influence cognitive processes. Will’s research explores cultural, environmental, and psychological influences on how people think and decide. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in the Department of Psychology. Will worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Adaptive Behavior and Cognition at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, and then in the Department of Psychology at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. His current interests concern the conflicting human needs for autonomy and community, and how that conflict is getting resolved among remote workers, freelancers, and other location-independent professionals.